In the digital era, when the vast majority of transactions are conducted electronically, it is perhaps surprising that paper checks remain the most popular business-to-business payment method.

While check use in the general population continues to wane, 80% of U.S. businesses steadily make at least some of their payments by check, finding that they align with their financial needs, preferences and workflows. This has led to vulnerability and a recent spike in check fraud.

Check theft isn't a new crime. Banks have been fighting check fraud for as long as checks have existed. In fact, in 1526, the city of Venice, Italy, banned checks outright because fraud was so rampant. With their lengthy process times and the relative ease with which they can be stolen, counterfeited and forged, checks have always been an attractive target for criminals.

However, the amount of money being lost to check fraud is today at historic highs. In 2022, banks saw a staggering 84% increase in check fraud according to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a specialist unit of the US Treasury Department.

The American Bankers Association has also raised the alarm, noting a steep rise in check fraud losses. In 2018 (the last year for which figures are available), losses totaled more than $1.3 billion. That’s a jump of more than half a billion dollars on the $789 million lost to check fraud in 2016.

In this article, we’ll shed light on the story behind the startling statistics and news headlines and answer common questions: Who is perpetrating these crimes? How are they managing to evade detection? Why is fraud continuing to rise? And, importantly, where there are opportunities in the journey of a stolen check to prevent, disrupt and expose this growing fraud threat.

Download the new Journey of a stolen check infographic

How checks are stolen

In February 2023, FinCEN issued an official alert about spiraling rates of check fraud.

“Despite the declining use of checks in the United States, criminals have been increasingly targeting the U.S. Mail since the COVID-19 pandemic to commit check fraud,” they wrote.

The U.S. mail system was named as the main area of concern.

In 2021, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service reported roughly 300,000 complaints of mail theft; an increase of 161% on the same period a year earlier.

The Covid-19 pandemic — and trillions of dollars in relief funds that were mailed out across the U.S. in the form of paper checks — proved to be a target that was too attractive for criminals to ignore. Perhaps as a result of those criminals looking for new sources of revenue when government stimulus payments were no longer an easy target, the problem has continued to grow since.

The FinCEN alert highlighted business payments as a particular source of concern: “Criminals will generally steal all types of checks in the U.S. Mail as part of a mail theft scheme, but business checks may be more valuable because business accounts are often well-funded and it may take longer for the victim to notice the fraud.”

The FinCEN alert highlighted business payments as a particular source of concern: “Criminals will generally steal all types of checks in the U.S. Mail as part of a mail theft scheme, but business checks may be more valuable because business accounts are often well-funded and it may take longer for the victim to notice the fraud.”

It also details the way these thefts are executed.

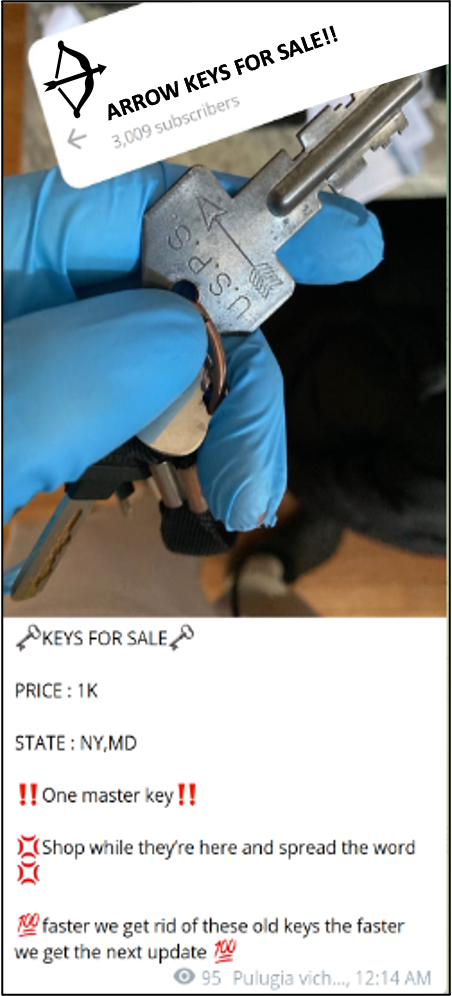

“Mail theft can occur through forced entry or the use of makeshift fishing devices, and increasingly involves the use of authentic or counterfeit USPS [United States Postal Service] master keys, known as arrow keys.”

Arrow keys are used by the Postal Service to collect the contents of USPS mailboxes. Both arrow keys and stolen checks have been found for sale online for as much as $1,000 in what experts believe is yet another sign that check fraud is becoming big business.

“It’s completely out of control,” says Frank Albergo, president of the Postal Police Officers Association. Postal services robberies only occurred 80 times in 2018, but now are almost a daily event, with letter carriers being robbed 717 times in fiscal 2022 and the first half of fiscal 2023, according to the USPS Postal Inspection Service.

In 95% of those cases, the criminals were looking for the arrow key, says Albergo.

Paul Benda, senior vice president of operational risk and cybersecurity at the American Bankers Association, has recently commented that “the mail system isn’t as secure as everyone thought it was,” adding that an audit report in 2020 found that Postal Service management controls over arrow keys were “ineffective,” increasing the risk that lost or stolen keys are not detected before they are used.

There have also been reported cases of postal employees being recruited by organized criminals to steal checks at sorting and distribution centers. In other instances, postal carriers have been robbed at gunpoint for their keys.

The ecosystem of a stolen check

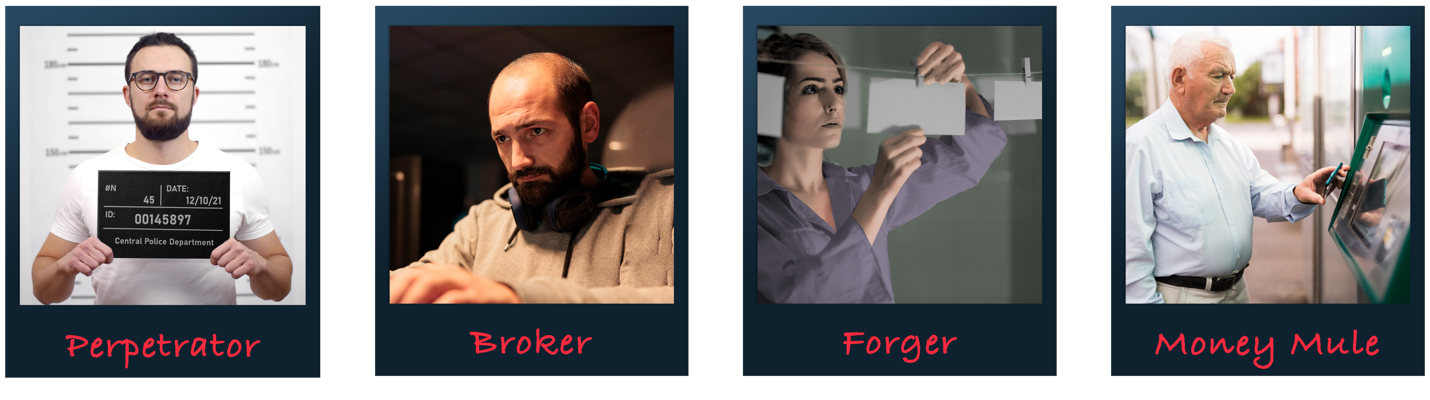

The Evidence-Based Cybersecurity Research Group at Georgia State University, calls the modern check fraud ecosystem “an elaborate supply chain”.

Whereas stealing checks was once a small-scale operation – criminals pilfering a check or two from residential mailboxes – a whole new group of perpetrators have moved in on the scene. Check fraud, he says, now resembles a much larger-scale enterprise, often with the involvement of organized crime.

1. The Initial Perpetrator

Motivations and profiles of check thieves

The overwhelming motivation for each person in the check fraud supply chain is financial. Check fraud is big business.

According to the FBI, 70% of U.S. organizations reported instances of check fraud during 2021, resulting in losses totaling more than $18 billion. And this upward trend shows no sign of slowing, with check fraud losses predicted to hit the $24 billion mark by the end of 2023.

It was reported in early 2022 that the prices being paid for stolen checks were typically $175 for personal checks and $250 for business ones with transactions usually made in Bitcoin. When checks are being stolen in such large numbers, it’s easy to see how the numbers can quickly add up.

For the initial perpetrator – the check thief – there is an almost guaranteed market for their stolen goods. In what many see as a key contributor to the record high rates of check fraud, there are easy ways of connecting to that market thanks to the proliferation of online platforms and encrypted messaging apps.

Techniques for obtaining personal information

For a stolen check to be successfully cashed, criminals require more than just the check itself: they may also need to obtain information about the recipient.

While techniques required for obtaining a check are more traditional – stealing items from mailboxes, offices, homes, purses or apartment building mailrooms – the techniques required to obtain personally identifiable information (PII) are usually more sophisticated.

The modern thief may need to know how to: skim devices on ATMs or point-of-sale terminals; operate phishing or social engineering scams, or; hack into financial institutions and databases.

2. The Broker

Once a thief has stolen checks and personal information in their possession, they will most likely sell them on to a broker – someone who acts as a middleperson and establishes a check trafficking network. With the help of encrypted messaging channels, the broker can connect with a forger who will be looking to acquire genuine, signed checks to ‘wash’.

3. The Forger

The role of the forger is to alter or counterfeit the stolen checks. Using a technique known as ‘check washing’, a forger will use easy-to-purchase chemicals, such as nail polish remover, to undetectably erase the original check amount and the intended payee’s name. With this information removed, the forger is then free to rewrite the check for a new sum – hundreds or thousands of dollars higher than the original amount – to whichever new payee name they choose.

Check forgers also use stolen checks to create templates that facilitate their fraudulent activities. After obtaining a genuine check through illicit means, they meticulously scan or photograph it, capturing all its unique elements, such as the bank's logo, account numbers, and signatures. Armed with this digital copy, they employ sophisticated graphic design software to meticulously recreate the check's layout and appearance. By altering the necessary fields, like the payee's name and the payment amount, they effectively create a seemingly legitimate template. Once the template is perfected, the forger can print multiple copies and utilize them in a multitude of fraud attempts; or sell this template online to other fraudsters. This sinister approach enables them to exploit the stolen check's information numerous times.

4. The Money Mule (Launderer)

The role of the money mule, or launderer, is to cash or deposit the forged check. Sometimes known as ‘walkers’, these are the people who actually walk into a bank and present the stolen check, impersonating genuine bank customers.

Money mules are chosen for their ability to seem ‘ordinary’ and ‘unsuspecting’ and will sometimes receive training on how to portray themselves as legitimate customers.

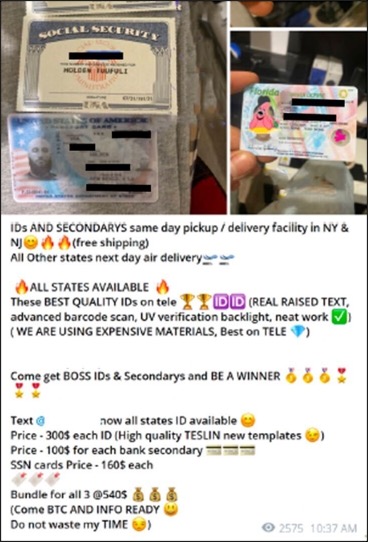

Some money mules are paid to receive stolen checks into their own bank accounts. They are then forced to withdraw or transfer the money back to the criminal gang behind the scam. Other times, walkers will be given fake identity documents which they use to set up a bank account into which the check can be paid – preventing law enforcement officials from tracing the account back to a real person

Again, it is online messaging apps and platforms that usually facilitate the recruitment of money mules. The messaging app, Telegram, in particular, has been identified as a fertile recruitment ground for organized crime groups looking for those willing to put themselves at risk of arrest if caught red-handed with a forged check.

According to Paul Benda, the elderly and homeless are often recruited as walkers because they are vulnerable, more likely to agree to take part in the crime for a low payout and – in the case of the elderly – are less likely to have their credibility questioned by the bank teller.

Brokers often accompany groups of walkers to the bank, having matched their age, race and gender to the names on the checks they are cashing. It’s even been known for brokers to buy clothes for walkers, or take them to the hair salon, to ensure they ‘look the part’.

Where additional verification is required, walkers will be given fake identification and documents that match the business or individual’s name they are presenting.

The fate of the stolen check data and images

Selling personal information

Dark web marketplaces and forums

The opportunity that presented itself to organized crime, when trillions of dollars of stimulus checks were mailed out during the pandemic, also happened to combine with another development that proved valuable to them: the growth of the dark web.

On the dark web, where encrypted traffic is sent through layers of relays around the globe, it is easy to hide behind anonymity and transact with other criminals looking to buy or sell stolen data and checks. And while law enforcement may be able to observe criminal exchanges, they are very unlikely to be able to trace the participants.

Research from Georgia State University’s Evidence-Based Cybersecurity Research Group found that an average of 1,325 stolen checks were being sold online in the dark web groups they observed in October 2021 – up from 409 in August 2021 and just 158 per week in October 2020. The group admits that these figures likely only represent a small fraction of the number of checks actually being exchanged given that their work was focused on just 60 of the thousands of black markets that are currently active.

Underground economy for personal data

Underground economy for personal data

While stolen checks themselves are hugely valuable, some criminals are going further and using the information found on the checks to harvest further profits. Checks contain a large amount of information, which means they are prime targets for criminals. From the data on checks, criminals can create fake accounts and open new lines of credit.

In some cases, criminals will utilize checks to steal the victim’s identity, using their name and address to manufacture fake driver’s licenses, passports and other legal documents. After taking over someone’s identity, a fraudster can use it to submit false applications for loans and credit cards, access the victim’s bank accounts and engage in other types of online fraud.

Exploitation of check images

Stolen checks are also sometimes scanned and uploaded for sale on the dark web to counterfeiters and forgers. These scanned, doctored images can then be uploaded for mobile deposit bypassing traditional fraud detection technology which cannot determine between authentic live checks and screenshot checks.

Consequences and impact

Financial losses

Rates of check fraud – and the subsequent losses incurred by American banks, businesses, and consumers – are at record highs.

Losses are keenly felt by victims and, in some circumstances, leave their accounts cleared out. Although victims are usually refunded by banks where check fraud occurs, banks can decline to cover a stolen check if a customer takes too long to report it or in cases where it is believes a customer was negligent.

Victims may also be impacted by delays in receiving restitution for critical losses. As banks struggle to keep up with a burgeoning number of cases, theft victims are, in some cases, waiting weeks or even months for their cases to be resolved.

But it’s not only funds stolen through the theft of the check that can cause loss, inconvenience and distress. Victims can be more deeply, additionally impacted by the sale of their PII. In the hands of criminals, this data can lead to account takeover attacks and identity theft.

Robin Pugh, President and CEO of cyber intelligence research company, DarkTower, has recently sounded the alert on this. “The rise of nefarious activities,” he observes, “has led to a proliferation of sensitive information being shared on criminal marketplaces and has increased the amount of identity theft and fraud taking place.”

Tests conducted jointly by Mitek and DarkTower uncovered images of stolen checks and customer data for sale online that put more than $10 million of customer funds at risk. The $10 million at-risk funds related to just one illicit marketplace and therefore represent only a fraction of the potential value of documents available on these exchanges, with experts estimating thousands of similar active markets. Where fraud had taken place, DarkTower found that losses averaged $50,000 per stolen document.

For financial institutions, there are significant direct – and indirect – costs to check fraud. That includes the costs of additional training, technology and more robust security measures to counter fraud attempts and the cost of reputational damage caused by publicity surrounding fraud failures.

Identity theft

Identity theft involves stealing an individual’s personally identifiable information and using that information as their own. Identity theft leaves victims with significant damage to their finances and reputation. It can result in bank accounts, credit cards, and loans being taken out in the person’s name, leaving the real person attached to that identity to deal with the damage to their finances, credit score and personal reputation long after the identity thief has moved on to their next victim.

Legal consequences

The criminal justice is catching up with some of the criminal gangs behind large-scale check fraud. In one case in Southern California last year, nearly sixty people were arrested on charges of committing more than $5 million in check fraud against 750 people. However, the growing scale of the problem means additional resources are needed to combat it.

Check out the revealing Journey of a stolen check visual infographic

Combating check theft

Awareness and education

In efforts to combat rising rates of check fraud, banks and authorities such as FinCEN have begun high-profile awareness-raising campaigns to educate check users on safer ways to make payments. That has included advising people not to mail checks where possible, and advice on how to do so safely if they do need to use the mail. (The advice is not to put packages containing checks into residential mailboxes: drop checks at a post office instead.)

Businesses have also been advised to, where available, opt into banks’ ‘positive pay’ services. Positive pay allows account holders to pre-authorize checks so that they can only be paid out to the intended payee and for specific, pre-authorized amounts.

Bank tellers are being provided with training on how to identify ‘walkers’ and ‘brokers’ and how to ask questions and request additional documentation that can identify suspicious deposits.

Technological solutions

Advanced technologies are available that can help banks effectively navigate the balancing act between convenience and safety. However, it’s important to note that, while various check fraud solutions can catch many types of check fraud, more basic solutions can also trigger tedious manual processes and false positives. This costs financial institutions time and money in additional analysts and custom data science platforms.

Check Fraud Defender from Mitek is designed to detect and prevent check fraud while also reducing the number of checks routed for manual review, limiting false positives. Using deep computational visual analysis, Check Fraud Defender can analyze checks from any channel – ATM, in-branch deposit or mobile deposit – getting in the way of fraudsters, whatever pathway they target.

Check Fraud Defender’s secure cloud-hosted environment uses patented computer vision technology and AI to analyze more than 20 unique check features, enabling banks to detect forgeries and process checks with greater accuracy and efficiency.

In addition to this, Mitek’s partnership with cyber threat researchers, DarkTower, now provides all customers of Mitek’s Check Fraud Defender access to data about compromised accounts.

Mitek uses DarkTower’s proprietary sourcing technology and its own state of the art image analysis technology to extract data from stolen documents such as checks, account screens, and identification documents sold on online channels and in marketplaces. This allows Mitek to deliver automated alerts for potentially compromised accounts to financial institutions.

Collaboration and legislation

Law enforcement agencies, financial institutions, and government bodies are working co-operatively to strengthen legal frameworks and regulations related to check fraud. That involves sharing information and insights into how these crimes are committed and where weak points reside that can be exploited by criminals so that solutions can be designed and implemented to combat threats.

Understanding the ecosystem and the bad actors involved is crucial for this as collective efforts, awareness, and technological advancements are key to minimizing check theft and safeguarding financial transactions.

Conclusion

Check theft is a multifaceted problem with far-reaching consequences. With 42% of all U.S B2B transactions still made by check, check fraud and the identity fraud that so often accompanies it, has the potential to deeply impact a large section of the population and cause banks and businesses deep, long-lasting reputational and financial damage. The journey of a stolen check is not always straight forward and can get hard to track – for a visual representation, download our infographic which outlines the same fraud ecosystem.